Half a life with foreign literature: Margarita Rudomino and her library

(1)(7).jpg)

The life of Margarita Rudomino is inseparably associated with the establishment and development of her library. Together they went a long way, from a cold and cramped room on Denezhny Pereulok to their own specially designed building on Nikoloyamskaya Street. Margarita Rudomino, with over 52 years devoted to her work, guaranteed that the entire world would know about her library.

Secondary school librarian

Margarita Rudomino’s first childhood memories were about Saratov, even though she was born in the small Polish town of Bialystok, which the family left after her birth. She was raised hearing German and French as her mother was a language teacher, and her father, an agronomist, spoke these languages too. Margarita’s parents were fans of foreign literature and always told their daughter that every educated person should speak another language in addition his native tongue.

-s-Adrianom.jpg)

.jpg)

Young Margarita visited Germany and France with her mother several times and after enrolling at a women’s gymnasium she became a local celebrity being the only of her peers who had been abroad. Her friends could listen to her stories about other countries for hours.

But when Margarita turned 14, her careless life was over. This is when both her parents passed away, almost at the same time, and when her aunts began raising her. Her new life was scary for the young girl was afraid that she would become a maid in her aunts’ house, much like other orphans portrayed in sentimental novels for girls of the 19th century.

But her fears did not come to pass: her aunts shared her love for languages and encouraged their niece’s hobby. Moreover, one of them, Yekaterina Kester, established foreign language courses and assigned Margarita accounting duties and to look after a small library. Margarita sometimes taught French herself and began studying English. After graduating from preparatory school she began working as a librarian at a non-classical secondary school where her mother once worked.

Fragmentfotografii1920.jpg)

In 1921, Margarita went to Moscow to enroll in the Romano-Germanic Department of the Social Sciences Faculty at Lomonosov Moscow State University.

Creator of neo-philological library

A new institute of neo-philology was about to appear in Moscow. It was supposed to have a large library, which would require a curator. Margarita Rudomino, then a reputed young expert from the Saratov library, was offered this position. She agreed but the institute failed to open. She was still eager to do the job and so she decided to reorganise the library. She had to knock on many a door at various agencies to receive permission for this. As she told them, “there are books and there are people who want to work with them.” But in response she heard only that there was no need for this during the such difficult times, people had other things to worry about than reading foreign literature. But eventually Margarita achieved her goal and opened a neo-philological library named after the institute in 1922.

There were not too many people who wanted to work there, including Margarita herself, in addition to three more librarians and even a cleaner. They built up the collection themselves and also acquired some literature from the Central Book Fund where books that belonged to former nobility were stored. Margarita also brought a huge collection of her mother’s books from Saratov. Those were mostly books on linguistics and teaching languages. All of them were moved to a small, cold and tiny room on Denezhny Pereulok, which was the only space they could get for the new library.

Writer and translator Kornei Chukovsky got interested in this project and decided to pay them a visit. When he arrived he saw an unsightly scene: a dark, damp room filled with wet, frost-bound books and among them a tiny young woman muffled up in an overcoat. At that moment, Chukovsky became a permanent reader of the library and saw to it that the collection would soon reach some 2,000 books.

And this number would steadily grow: in 1923, the Ostrovsky Library presented some 12,000 foreign literature books to Margarita’s library, which also received books straight from Berlin for which several rooms in the Historical Museum were provided. This was another small victory. The neo-philological library became a place where Moscow intelligentsia loved to convene and hold themed evenings, which writers, translators and linguists alike would attend. Since many of them wanted to see more foreign journals in the library, Margarita found a way to fulfill their wish.

Margarita was acquainted with Clara Zetkin, a revolutionary and one of the founders of the Communist Party of Germany. Knowing that the influential German regularly received foreign newspapers and journals, Margarita asked her for help. Zetkin liked the idea, and told Margarita:

“Come to my room, young lady and don’t be shy if I’m sleeping or taking a nap,” Zetkin said. “Take newspapers and journals, but only those to the left of the chair, those I have already read. Do not touch those on the right yet for I have not read them, and my entire life is in them. So, if I am sleeping or resting, just come in and take whatever you want from the pile on the left.”

In the meantime, Margarita’s personal life had experienced some change: she married editor and teacher Vasily Moskalenko. The newlyweds took double surnames: Rudomino-Moskalenko and Moskalenko-Rudomino. They had two children: Marianna and Adrian. Her son was given the last name Rudomino to preserve her ancient family name.

New home

Things were not going smoothly at the library. In 1924, Anatoly Lunacharsky took a liking to the room in Denezhny Pereulok and the attic where Rudomino lived and she was forced to move out. The library was left without a home and was temporarily closed until it received a small space in the Historical Museum.

In the same year, the library was named the State Library for Foreign Literature. It became a place to read books and also to learn foreign languages: in a year’s time, several language courses opened there, which were taught by professional teachers. Margarita Rudomino closely monitored the development of the classes, which required even more space. The library first moved to the State Academy of Fine Arts and then to the former apartment of MSU Professor Yury Sergiyevsky. The new location housed a reading hall, a reference and bibliographical department, and rooms to host language classes.

In 1926, another important event happened: higher foreign language courses were launched there. Margarita herself began training at the library science courses at the MSU academic libraries faculty. She went on working trips to Germany and France, while training teachers and translators at her library. She dreamed of making the library known and organising mobile foreign literature libraries at enterprises. Many of them agreed.

In 1928, the library had over 40,000 books, including books in English, French, German, Polish, Italian, Spanish and other languages. Such a large collection again required more space. The next home of the library was the Cosmas and Damian Church on Stoleshnikov Pereulok.

New Name

By the time the library marked its 10th anniversary it was already known around the entire USSR. In 1932, it was renamed the State Central Library for Foreign Literature. The higher foreign language courses were so popular and respected that they transformed into a separate institution, the Moscow Institute of Foreign Languages, which is currently known as the Moscow State Linguistic University.

The times of political repressions orchestrated by Joseph Stalin were hard. In 1936-1938, three employees of the library were arrested for allegedly wrongful hiring procedures; ‘ideologically wrong’ publications were found at the library.

“For instance, why is this book provided to the readers? Are you promoting bourgeois ideas? - they would say. And another commission looked at the same book a month later and accused us of depriving the people of a good, useful book…This pendulum was swinging back and forth all the time,” Margarita Rudomino recalled later.

She luckily avoided repression, but in 1938 she was on the verge of being persecuted: one of the former employees reported her to authorities. The case did not go beyond accusations, and the board of the Main Directorate for Research, Art and Museum Institutions stood up for the library.

But there was good news as well. For instance, in 1948, the Second Spanish Republic presented the library with a collection of books in Spanish.

Centre for anti-Nazi propaganda

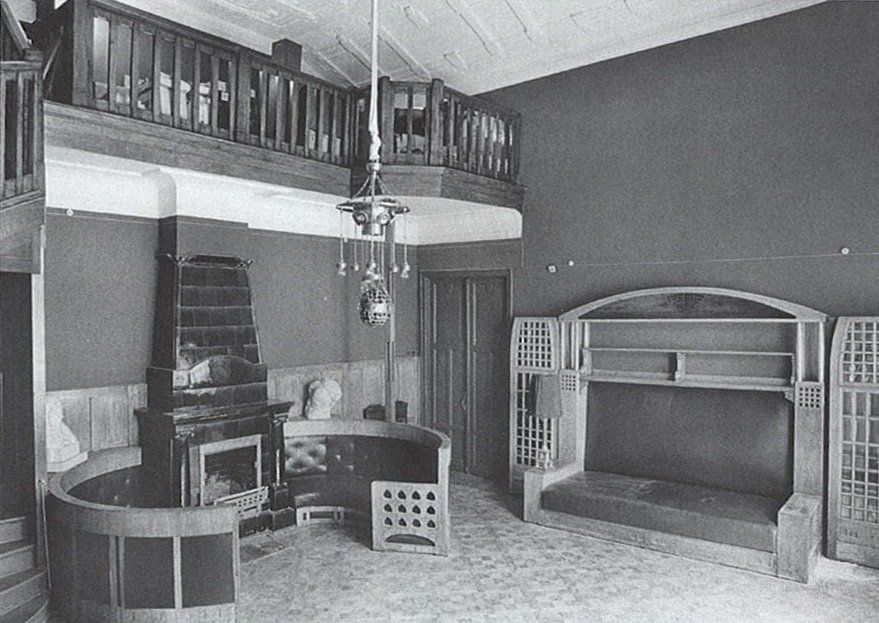

Margarita Rudomino did not close the library during the Great Patriotic War. The most valuable books were sent beyond the Ural Mountains and the library was turned into a centre for anti-Nazi propaganda. The military were permanent guests there – they were taught to read in German and translated documents captured from the enemy. building was damaged during an airstrike and the library temporarily moved to a mansion in Lopukhinsky Pereulok.

After the war, many trophy books moved to the library. Margarita visited Germany in 1945 and spent six months there with her employees saving books from the ruined German libraries. In 1946, the library received a gift of one million books in English from the United States. Only some of them remained in the library, the rest were given to regional libraries. Margarita Rudomino also decided to join the State Publishing House of Foreign Literature so that she could receive state support. Soon enough, the library had over 400,000 books and had subscribed to foreign newspapers and magazines. And then there was another move, this time to a building on Razina Street.

In 1948, Margarita Rudomino’s library was named the All-Union State Library for Foreign Literature. Books were provided to ministries, publishing houses and government agencies. The founder only admitted the best books and selected them very carefully.

Library finds a home after 44 years

All this time, Margarita Rudomino had been about receiving her own building for the library. She wanted to be sure that nobody would catch her off guard and ask to move out. There were also rumours that the building on Razina Street would soon be demolished for the construction of a hotel. They could not close the library itself, for it had become way too important and famous.

Finally, her dream came true: in 1952, the USSR Council of Ministers issued a decree about the construction of a library building. They picked up a remote plot of land, but Margarita rejected it. She wrote: “We were offered a land plot near Baltiiskaya Street, beyond Sokol. There were many deserted land plots, and one of them was ours. I felt that if I agreed or begin consulting with somebody, the Mossovet Presidium would issue a ruling and the library would be closed.”

It took them a while to find another spot and there were other certain difficulties. Finally, in 1961, the construction began on Ulyanova Street (currently Nikoloyamskaya). Four years later, the library moved there. Margarita liked everything at the new place: a spacious storage room, 14 reading halls and a conference hall. At the time, the library employed 700 people.

“I might seem sentimental, but I must confess that when I saw how my long-suffering books twere moved from place to place, suffering from dampness and cold, finally found their home in a repository, I could not help but kiss them,” Margarita Rudomino said.

She received messages of congratulations from all over the Soviet Union. One of them was from Kornei Chukovsky. He was interested in what was going on at the library, which he loved since the days when it was located on Denezhny Pereulok. In his message, Chukovsky called Margarita “the queen of palace chambers and ruler of books in 120 languages.”

First Vice President

A new life had begun. Margarita Rudomino frequently went on business trips to France. She was recognised not only by her French colleagues: in 1973, representatives of the international library community, who came to attend the 36th General Conference of the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA), visited the library. Being First Vice President of IFLA, Margarita Rudomino represented Soviet libraries at the highest levels. In 1973, she received the lifetime status of honorary Vice President of IFLA, while a year before the library was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labour.

That same year, Rudomino was released of her duties at her own library and was ordered to take mandatory retirement. She was replaced by Lyudmila Kosygina, the daughter of the chair of the USSR Council of Ministers. Margarita was deeply affected by the loss of her creation. Both library employees and readers said that the decision was wrong and that Margarita still had enough energy to create another library. Kosygina was unofficially prohibited from speaking about her predecessor.

Margarita Rudomino died in April 1990. In August of that year, library workers asked the USSR Council of Ministers to name the library after its founder.

Library today

The collection of the All-Russian State Library for Foreign Literature currently includes over 1.5 million books. It also has a bookstore and a cinema.

Since 2017, the library has been holding themed festivals, with the most popular being the one for enthusiasts of the French language. The library has the Rudomino Academy, which trains Russian and foreign cultural workers, as well as the American Cultural Centre and the Centre of Slavic Cultures. Among the library’s partners are the Bulgarian Cultural Institute, the Azerbaijani Cultural Centre, the Netherlands Education Support Office and the department of Japanese culture, among others.

The library takes an active part in city programmes, in particular, in the annual Library Night event.

The 120th anniversary of birth of Margarita Rudomino will be marked at the Library for Foreign Literature not only on 3 July. In the autumn, the library will hold many events, see its website.